In the Reading, Virtues Are Described as a ___________ Between ___________ & ______________?

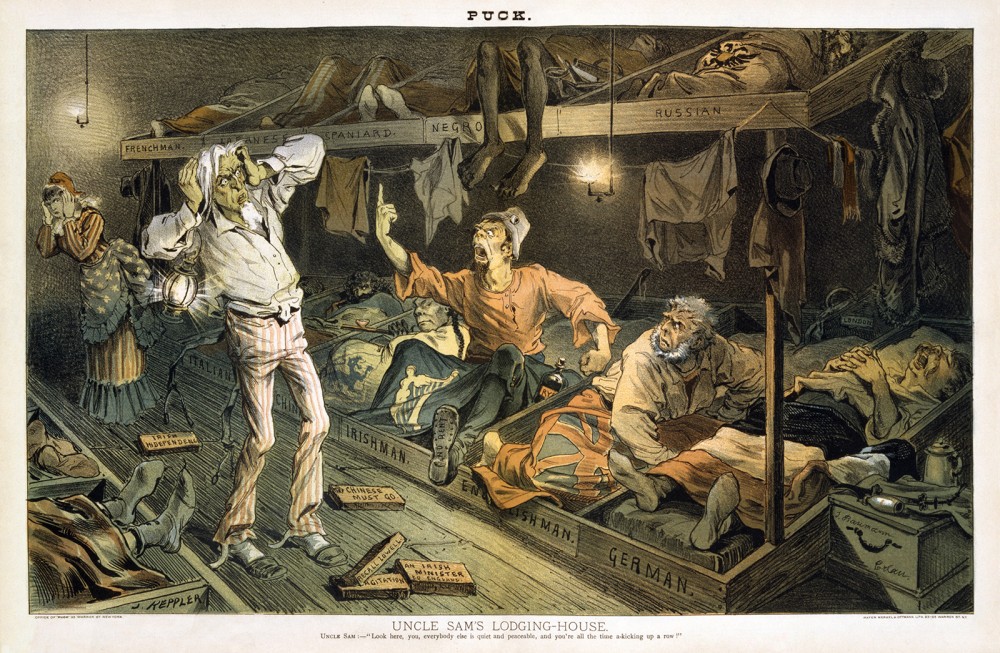

A political drawing in Puck magazine on January 25, 1899, captures the heed-set of American imperialists. Library of Congress.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this affiliate.*

- I. Introduction

- II. Patterns of American Interventions

- Three. 1898

- Four. Theodore Roosevelt and American Imperialism

- 5. Women and Imperialism

- 6. Immigration

- VII. Conclusion

- VIII. Main Sources

- Nine. Reference Material

I. Introduction

The discussion empire might conjure images of ancient Rome, the Farsi Empire, or the British Empire—powers that depended variously on military conquest, colonization, occupation, or directly resource exploitation—but empires can take many forms and imperial processes can occur in many contexts. One hundred years after the Us won its independence from the British Empire, had it go an empire of its ain?

In the decades later on the American Civil War, the U.s. exerted itself in the service of American interests around the earth. In the Pacific, Latin America, and the Center Eastward, and most explicitly in the Spanish-American War and under the foreign policy of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, the United States expanded on a long history of exploration, trade, and cultural exchange to do something that looked remarkably like empire. The question of American imperialism, then, seeks to understand not only direct American interventions in such places equally Cuba, the Philippines, Hawaii, Guam, and Puerto Rico, simply also the deeper history of American engagement with the wider world and the subsequent ways in which American economic, political, and cultural power has shaped the deportment, choices, and possibilities of other groups and nations.

Meanwhile, as the United states asserted itself abroad, it acquired increasingly higher numbers of foreign peoples at home. European and Asian immigrants poured into the United States. In a sense, imperialism and immigration raised like questions virtually American identity: Who was an "American," and who wasn't? What were the nation'south obligations to foreign powers and strange peoples? And how attainable—and how fluid—should American identity be for newcomers? All such questions confronted late-nineteenth-century Americans with unprecedented urgency.

Two. Patterns of American Interventions

American interventions in United mexican states, Communist china, and the Eye East reflected the The states' new eagerness to arbitrate in foreign governments to protect American economical interests abroad.

The United States had long been involved in Pacific commerce. American ships had been traveling to China, for instance, since 1784. As a per centum of full American strange trade, Asian merchandise remained comparatively small, and yet the idea that Asian markets were vital to American commerce affected American policy and, when those markets were threatened, prompted interventions.1 In 1899, secretary of country John Hay articulated the Open Door Policy, which called for all Western powers to have equal access to Chinese markets. Hay feared that other imperial powers—Japan, Great Britain, Germany, France, Italia, and Russian federation—planned to carve China into spheres of influence. It was in the economic involvement of American business to maintain China for free merchandise. The following year, in 1900, American troops joined a multinational force that intervened to foreclose the closing of trade by putting down the Boxer Rebellion, a motion opposed to strange businesses and missionaries operating in China. President McKinley sent the U.S. Army without consulting Congress, setting a precedent for U.South. presidents to order American troops to action effectually the globe under their executive powers.2

The U.s. was not just ready to intervene in foreign affairs to preserve foreign markets, it was willing to take territory. The United States acquired its first Pacific territories with the Guano Islands Act of 1856. Guano—collected bird excrement—was a popular fertilizer integral to industrial farming. The human activity authorized and encouraged Americans to venture into the seas and claim islands with guano deposits for the United States. These acquisitions were the beginning insular, unincorporated territories of the United States: they were neither part of a state nor a federal district, and they were not on the path to always attain such a status. The act, though little known, offered a precedent for futurity American acquisitions.3

Merchants, of class, weren't the only American travelers in the Pacific. Christian missionaries soon followed explorers and traders. The first American missionaries arrived in Hawaii in 1820 and Mainland china in 1830, for example. Missionaries, though, often worked aslope business organisation interests, and American missionaries in Hawaii, for case, obtained large tracts of land and started lucrative sugar plantations. During the nineteenth century, Hawaii was ruled past an oligarchy based on the sugar companies, together known as the "Big Five." This white American (haole) aristocracy was extremely powerful, but they still operated outside the formal expression of American state power.iv

As many Americans looked for empire across the Pacific, others looked to Latin America. The United States, long a participant in an increasingly complex network of economic, social, and cultural interactions in Latin America, entered the tardily nineteenth century with a new aggressive and interventionist attitude toward its southern neighbors.

American capitalists invested enormous sums of money in Mexico during the tardily nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, during the long reign of the corrupt withal stable authorities of the modernization-hungry president Porfirio Diaz. But in 1910 the Mexican people revolted against Díaz, ending his disciplinarian government but too his friendliness toward the concern interests of the U.s.a.. In the midst of the terrible devastation wrought by the fighting, Americans with investment interests pleaded for governmental assist. Simply the U.Due south. government tried to control events and politics that could not be controlled. More and more American businessmen chosen for military intervention. When the brutal strongman Victoriano Huerta executed the revolutionary, democratically elected president Francisco Madero in 1913, newly inaugurated American president Woodrow Wilson put force per unit area on Mexico's new government. Wilson refused to recognize the new authorities and demanded that Huerta footstep aside and allow free elections to take identify. Huerta refused.five

When Mexican forces mistakenly arrested American sailors in the port city of Tampico in April 1914, Wilson saw the opportunity to apply additional pressure on Huerta. Huerta refused to make amends, and Wilson therefore asked Congress for authority to apply force against Mexico. Simply even before Congress could reply, Wilson invaded and took the port metropolis of Veracruz to prevent, he said, a German shipment of artillery from reaching Huerta's forces. The Huerta authorities cruel in July 1914, and the American occupation lasted until November, when Venustiano Carranza, a rival of Huerta, took power. When Wilson threw American support backside Carranza, and non his more than radical and now-rival Pancho Villa, Villa and several hundred supporters attacked American interests and raided the town of Columbus, New Mexico, in March 1916, and killed over a dozen soldiers and civilians. Wilson ordered a castigating expedition of several thousand soldiers led past General John J. "Blackjack" Pershing to enter northern Mexico and capture Villa. But Villa eluded Pershing for nearly a year and, in 1917, with war in Europe looming and great injury done to U.S.-Mexican relations, Pershing left United mexican states.6

The United States' deportment during the Mexican Revolution reflected long-standing American policy that justified interventionist actions in Latin American politics because of their potential bearing on the United States: on citizens, on shared territorial borders, and, mayhap most significantly, on economic investments. This example highlights the role of geography, or perhaps proximity, in the pursuit of imperial outcomes. Simply American interactions in more distant locations, in the Middle East, for instance, look quite different.

In 1867, Mark Twain traveled to the Middle Due east as part of a large tour group of Americans. In his satirical travelogue, The Innocents Abroad, he wrote, "The people [of the Middle East] stared at u.s. everywhere, and we [Americans] stared at them. We mostly made them feel rather small, as well, before we got washed with them, because we bore down on them with America's greatness until we crushed them."seven When Americans later on intervened in the Middle East, they would exercise then convinced of their ain superiority.

The U.S. government had traditionally had little contact with the Heart East. Trade was limited, too limited for an economic relationship to exist deemed vital to the national involvement, merely treaties were all the same signed between the U.Due south. and powers in the Eye Eastward. Withal, the bulk of American involvement in the Eye East prior to Globe War I came not in the course of trade only in education, scientific discipline, and humanitarian assistance. American missionaries led the way. The first Protestant missionaries had arrived in 1819. Soon the American Lath of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and the boards of missions of the Reformed Church of America became dominant in missionary enterprises. Missions were established in most every country of the Eye East, and even though their efforts resulted in relatively few converts, missionaries helped establish hospitals and schools, and their work laid the foundation for the establishment of Western-fashion universities, such every bit Robert College in Istanbul, Turkey (1863), the American Academy of Beirut (1866), and the American University of Cairo (1919).8

Iii. 1898

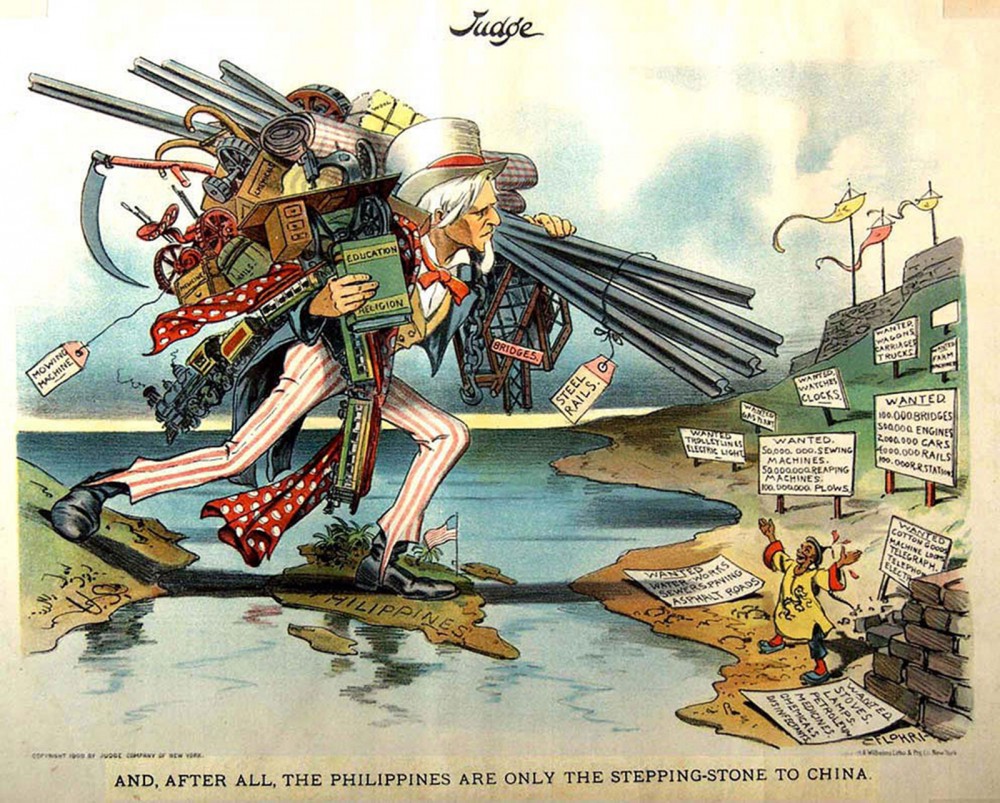

In this political drawing, Uncle Sam, loaded with the implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to cross the Pacific to Cathay, which excitedly awaits Sam'southward inflow. Such cartoons captured Americans' growing infatuation with imperialist and expansionist policies. C. 1900–1902. Wikimedia.

Although the United States had a long history of international economical, military, and cultural engagement that stretched back deep into the eighteenth century, the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (1898–1902) marked a crucial turning point in American interventions abroad. In pursuing war with Spain, and so engaging in counterrevolutionary conflict in the Philippines, the United States expanded the scope and forcefulness of its global reach. Over the adjacent two decades, the The states would become increasingly involved in international politics, particularly in Latin America. These new conflicts and ensuing territorial problems forced Americans to confront the ideological elements of imperialism. Should the Usa act as an empire? Or were foreign interventions and the taking of territory antithetical to its founding democratic ideals? What exactly would exist the relationship between the The states and its territories? And could colonial subjects be successfully and safely incorporated into the trunk politic equally American citizens? The Castilian-American and Philippine-American Wars brought these questions, which had ever lurked behind discussions of American expansion, out into the open.

In 1898, Americans began in hostage to turn their attention southward to problems plaguing their neighbor Cuba. Since the centre of the nineteenth century, Cubans had tried unsuccessfully again and again to proceeds independence from Spain. The latest uprising, and the one that would testify fatal to Spain's colonial designs, began in 1895 and was still raging in the winter of 1898. By that fourth dimension, in an attempt to crush the uprising, Castilian general Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau had been conducting a policy of reconcentration—forcing Cubans living in sure cities to relocate en masse to military camps—for about two years. Prominent paper publishers sensationalized Spanish atrocities. Cubans in the United States and their allies raised cries of Cuba Libre! And while the U.Due south. regime proclaimed a wish to avert armed conflict with Spain, President McKinley became increasingly concerned most the prophylactic of American lives and property in Cuba. He ordered the battleship Maine to Havana harbor in January 1898.

The Maine sabbatum undisturbed in the harbor for most ii weeks. And so, on the evening of February fifteen, a titanic explosion tore open the ship and sent it to the lesser of the ocean. Three quarters of the ship's 354 occupants died. A naval board of inquiry immediately began an investigation to ascertain the crusade of the explosion, but the loudest Americans had already decided that Spanish treachery was to blame. Capitalizing on the outrage, "yellow journals"—newspapers that promoted sensational stories, notoriously at the cost of accurateness—such every bit William Randolph Hearst'southward New York Journal chosen for war with Spain. When urgent negotiations failed to produce a mutually agreeable settlement, Congress officially declared war on April 25.

Although America's war attempt began haphazardly, Espana's decaying military crumbled. Military victories for the United States came quickly. In the Pacific, on May 1, Commodore George Dewey engaged the Spanish fleet exterior Manila, the capital letter of the Philippines (another Spanish colonial possession), destroyed it, and proceeded to blockade Manila harbor. Two months later, American troops took Cuba'southward San Juan Heights in what would become the well-nigh well-known battle of the state of war, winning fame not for regular soldiers only for the irregular, especially Theodore Roosevelt and his Crude Riders. Roosevelt had been the assistant secretary of the navy simply had resigned his position in guild to run into action in the war. His actions in Cuba fabricated him a national celebrity. As affliction began to consume away at American troops, the Castilian suffered the loss of Santiago de Cuba on July 17, finer ending the state of war. The two nations agreed to a cease-fire on August 12 and formally signed the Treaty of Paris in December. The terms of the treaty stipulated, among other things, that the United States would larn Spain's one-time holdings of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

Secretary of state John Hay memorably referred to the conflict as a "splendid little war," and at the time information technology certainly appeared that way. Fewer than four hundred Americans died in battle in a war that lasted about fifteen weeks. Contemporaries celebrated American victories equally the providential act of God. The influential Brooklyn government minister Lyman Abbott, for instance, alleged that Americans were "an elect people of God" and saw divine providence in Dewey'south victory at Manila.nine Some, such equally Senator Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana, took matters one step further, seeing in American victory an opportunity for imperialism. In Beveridge's view, America had a "mission to perform" and a "duty to belch" around the world.10 What Beveridge envisioned was nothing less than an American empire.

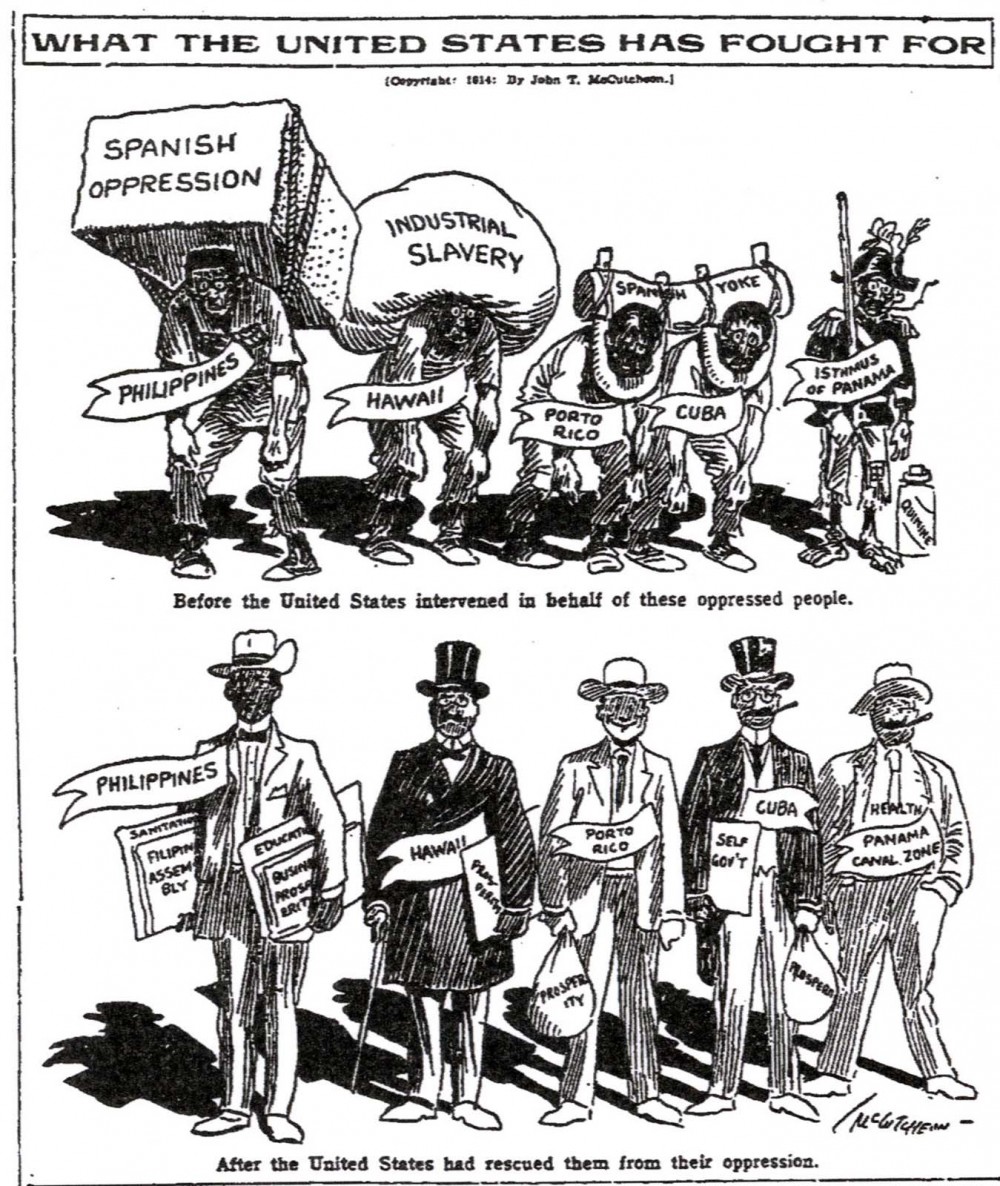

This 1914 political cartoon shows embodiments of colonies and territories earlier and after American interventions. The differences are obvious and exaggerated, with the pinnacle figures described as "oppressed" by the weight of industrial slavery until America "rescued" them, turning them into the respectable and successful businessmen seen on the bottom one-half. Those who claimed that American imperialism brought civilization and prosperity to destitute peoples used such visuals to back up their cause. Wikimedia.

But the question of whether the United States should become an empire was sharply debated across the nation in the backwash of the Spanish-American State of war and the acquisition of Hawaii in July 1898. At the bidding of American businessmen who had overthrown the Hawaiian monarchy, the United States annexed the Hawaiian Islands and their rich plantations. Between Hawaii and a number of former Castilian possessions, many Americans coveted the economic and political advantages that increased territory would bring. Those opposed to expansion, however, worried that imperial ambitions did not accord with the nation's founding ideals. American deportment in the Philippines brought all of these discussions to a head.

The Philippines were an afterthought of the Spanish-American War, but when the smoke cleared, the United States found itself in possession of a key foothold in the Pacific. After Dewey'southward victory over the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay, conversations nearly how to proceed occupied the attentions of President McKinley, political leaders from both parties, and the popular press. American and Philippine forces (under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo) were in communication: Would the Americans offer their support to the Filipinos and their ongoing efforts against the Spanish? Or would the Americans replace the Castilian as a colonial occupying force? American forces were instructed to secure Manila without allowing Philippine forces to enter the Walled City (the seat of the Spanish colonial government), hinting, perhaps, at things to come. Americans wondered what would happen next. Possibly a good many ordinary Americans shared the bewildered sentiments of Mr. Dooley, the fictional Irish gaelic-American barkeeper whom humorist Finley Peter Dunne used to satirize American life: "I don't know what to do with th' Ph'lippeens anny more than sparse I did las' summertime, befure I heerd tell iv thim. . . . We can't sell thim, nosotros can't ate thim, an' we can't throw thim into the thursday' aisle whin no wan is lookin''."11

Equally debates about American imperialism continued against the backdrop of an upcoming presidential ballot, tensions in the Philippines escalated. Emilio Aguinaldo was inaugurated every bit president of the Commencement Philippine Commonwealth (or Malolos Republic) in belatedly January 1899; fighting between American and Philippine forces began in early Feb; and in April 1899, Congress ratified the 1898 Treaty of Paris, which concluded the Spanish-American War and gave Spain $xx 1000000 in exchange for the Philippine Islands.12

Like the Cubans, Filipinos had waged a long state of war against their Spanish colonizers. The United States could have given them the independence they had long fought for, but, instead, at the bidding of President William McKinley, the United States occupied the islands and from 1899 to 1902 waged a bloody serial of conflicts against Filipino insurrectionists that cost far more lives than the war with Kingdom of spain. Under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo, Filipinos who had fought for freedom against the Spanish now fought for freedom against the very nation that had claimed to have liberated them from Spanish tyranny.13

The Philippine Insurrection, or the Philippine-American War, was a brutal conflict of occupation and insurgency. Contemporaries compared the guerrilla-style warfare in challenging and unfamiliar terrain to the American experiences in the so-chosen Indian Wars of the late nineteenth century. Many commented on its brutality and the uncertain mission of American troops. An April 1899 dispatch from a Harper's Weekly correspondent began, "A calendar week has passed—a week of fighting and marching, of jungles and rivers, of incident and take a chance and then varied and of so rapid transition that to sit down to write near information technology makes one feel as if he were trying to depict a dream where fourth dimension, space, and all the logical sequences of ordinary life are upset in the unrelenting brutality of state of war."xiv John Bass described his experiences in detail, and his reportage, combined with accounts that came directly from soldiers, helped shape public cognition about the state of war. Reports of cruelty on both sides and a few high-contour military investigations ensured connected public attention to events across the Pacific.

Amid fighting to secure the Philippine Islands, the federal government sent two Philippine Commissions to assess the situation in the islands and make recommendations for a civilian colonial government. A noncombatant administration, with William H. Taft equally the first governor-general (1901–1903), was established with military back up. Although President Theodore Roosevelt declared the war to be over in 1902, resistance and occasional fighting connected into the second decade of the twentieth century.15

Debates about American imperialism dominated headlines and tapped into core ideas about American identity and the proper role of the United States in the larger world. Should a one-time colony, established on the principles of liberty, liberty, and sovereignty, become a colonizer itself? What was imperialism, anyhow? Many framed the Filipino conflict as a Protestant, civilizing mission. Others framed American imperialism in the Philippines as naught new, every bit but the extension of a never-ending w American expansion. It was simply destiny. Some saw imperialism equally a way to reenergize the nation by asserting national say-so and power around the earth. Others baldly recognized the opportunities the Philippine Islands presented for access to Asian markets. But critics grew loud. The American Anti-Imperialist League, founded in 1899 and populated by such prominent Americans as Mark Twain, Andrew Carnegie, and Jane Addams, protested American imperial actions and articulated a platform that decried strange subjugation and upheld the rights of all to self-governance. Nonetheless others embraced anti-imperialist stances because of concerns virtually immigration and American racial identity, afraid that American purity stood imperiled by contact with foreign and foreign peoples. For whatsoever reason, however, the onset or acceleration of imperialism was a controversial and landmark moment in American history. America had become a preeminent force in the world.

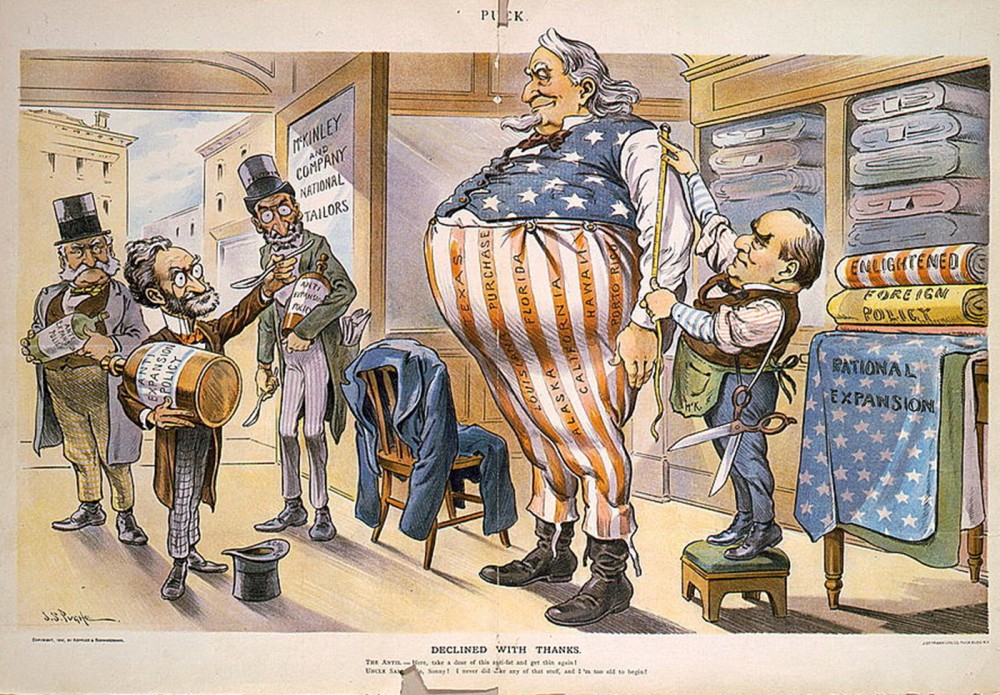

In this 1900 political cartoon, President McKinley measures an obese Uncle Sam for larger clothing, while anti-expansionists like Joseph Pulitzer unsuccessfully offer him a weight-loss elixir. Equally the nation increased its imperialistic presence and mission, many worried that America would grow too large for its own good. Wikimedia.

Iv. Theodore Roosevelt and American Imperialism

Under the leadership of President Theodore Roosevelt, the The states emerged from the nineteenth century with ambitious designs on global ability through armed services might, territorial expansion, and economic influence. Though the Spanish-American War had begun under the administration of William McKinley, Roosevelt—the hero of San Juan Hill, assistant secretarial assistant of the navy, vice president, and president—was arguably the most visible and influential proponent of American imperialism at the turn of the century. Roosevelt's emphasis on developing the American navy, and on Latin America as a primal strategic area of U.S. foreign policy, would have long-term consequences.

In render for Roosevelt's back up of the Republican nominee, William McKinley, in the 1896 presidential election, McKinley appointed Roosevelt every bit assistant secretary of the navy. The head of the department, John Long, had a competent simply lackadaisical managerial style that immune Roosevelt a corking deal of freedom that Roosevelt used to network with such luminaries equally military theorists Alfred Thayer Mahan and naval officer George Dewey and politicians such as Henry Cabot Lodge and William Howard Taft. During his tenure he oversaw the construction of new battleships and the implementation of new technology and laid the groundwork for new shipyards, all with the goal of projecting America'south ability beyond the oceans. Roosevelt wanted to aggrandize American influence. For instance, he advocated for the annexation of Hawaii for several reasons: it was within the American sphere of influence, it would deny Japanese expansion and limit potential threats to the West Coast, it had an excellent port for battleships at Pearl Harbor, and information technology would human activity as a fueling station on the mode to pivotal markets in Asia.16

Teddy Roosevelt, a politician turned soldier, gained fame after he and his Rough Riders took San Juan Hill. Images like this poster praised Roosevelt and the battle as Americans celebrated a "splendid petty state of war." 1899. Wikimedia.

Roosevelt, subsequently winning headlines in the state of war, ran as vice president under McKinley and rose to the presidency after McKinley'south assassination by the anarchist Leon Czolgosz in 1901. Among his many interventions in American life, Roosevelt acted with vigor to aggrandize the military, bolstering naval power specially, to protect and promote American interests abroad. This included the construction of eleven battleships between 1904 and 1907. Alfred Thayer Mahan'southward naval theories, described in his The Influence of Sea Power upon History, influenced Roosevelt a corking deal. In dissimilarity to theories that advocated for commerce raiding, coastal defense, and small "brown water" ships, the imperative to control the body of water required battleships and a "blue water" navy that could appoint and win decisive battles with rival fleets. Every bit president, Roosevelt continued the policies he established as assistant secretary of the navy and expanded the U.S. fleet. The mission of the Peachy White Fleet, sixteen all-white battleships that sailed around the world between 1907 and 1909, exemplified America's new ability.17

Roosevelt insisted that the "large stick" and the persuasive power of the U.S. war machine could ensure U.S. hegemony over strategically important regions in the Western Hemisphere. The U.s.a. used military intervention in diverse circumstances to further its objectives, just information technology did non have the power or the inclination to militarily impose its will on the entirety of Due south and Central America. The United States therefore more often used breezy methods of empire, such equally so-chosen dollar affairs, to assert dominance over the hemisphere.

The United States actively intervened again and again in Latin America. Throughout his time in office, Roosevelt exerted U.South. control over Cuba (even later it gained formal independence in 1902) and Puerto Rico, and he deployed naval forces to ensure Panama's independence from Colombia in 1903 in order to acquire a U.S. Canal Zone. Furthermore, Roosevelt pronounced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904, proclaiming U.S. law power in the Caribbean. Every bit articulated by President James Monroe in his almanac accost to Congress in 1823, the United States would treat whatsoever armed services intervention in Latin America past a European power equally a threat to American security. Roosevelt reaffirmed the Monroe Doctrine and expanded information technology by declaring that the Usa had the right to preemptive activity through intervention in any Latin American nation in order to correct administrative and fiscal deficiencies.18

Roosevelt's policy justified numerous and repeated police actions in "dysfunctional" Caribbean area and Latin American countries by U.S. Marines and naval forces and enabled the founding of the naval base of operations at Guantanamo Bay, Republic of cuba. This approach is sometimes referred to every bit gunboat diplomacy, wherein naval forces and Marines land in a national majuscule to protect American and Western personnel, temporarily seize control of the regime, and dictate policies friendly to American business, such equally the repayment of foreign loans. For example, in 1905 Roosevelt sent the Marines to occupy the Dominican Republic and established financial supervision over the Dominican government. Imperialists oftentimes framed such actions as almost humanitarian. They celebrated white Anglo-Saxon societies such as those establish in the Us and the British Empire as advanced practitioners of nation-edifice and civilization, helping to uplift debtor nations in Latin America that lacked the manly qualities of discipline and cocky-control. Roosevelt, for instance, preached that it was the "manly duty" of the United States to exercise an international police ability in the Caribbean area and to spread the benefits of Anglo-Saxon civilization to inferior states populated past inferior peoples. The president'southward language, for instance, contrasted debtor nations' "impotence" with the The states' civilizing influence, belying new ideas that associated self-restraint and social stability with Anglo-Saxon manliness.nineteen

Dollar diplomacy offered a less costly method of empire and avoided the troubles of military occupation. Washington worked with bankers to provide loans to Latin American nations in substitution for some level of command over their national fiscal diplomacy. Roosevelt first implemented dollar diplomacy on a vast scale, while Presidents Taft and Wilson continued the do in various forms during their own administrations. All confronted instability in Latin America. Rising debts to European and American bankers immune for the inroads of modernistic life but destabilized much of the region. Bankers, kickoff with financial houses in London and New York, saw Latin America equally an opportunity for investment. Lenders took advantage of the region's newly formed governments' need for cash and exacted punishing interest rates on massive loans, which were and so sold off in pieces on the secondary bond market. American economic interests were now closely aligned with the region just also further undermined by the chronic instability of the region's newly formed governments, which were ofttimes plagued past mismanagement, civil wars, and war machine coups in the decades post-obit their independence. Turnover in regimes interfered with the repayment of loans, equally new governments often repudiated the national debt or forced a renegotiation with suddenly powerless lenders.20

Creditors could not force settlements of loans until they successfully lobbied their own governments to become involved and forcibly collect debts. The Roosevelt administration did non want to deny the Europeans' rightful demands of repayment of debt, merely it also did not want to encourage European policies of conquest in the hemisphere as part of that debt collection. U.Southward. policy makers and military machine strategists within the Roosevelt assistants determined that this European practice of military intervention posed a serious threat to American interests in the region. Roosevelt reasoned that the United states must create and maintain financial and political stability within strategically important nations in Latin America, particularly those affecting routes to and from the proposed Panama Culvert. As a result, U.Due south. policy makers considered intervention in places similar Cuba and the Dominican Republic a necessity to ensure security around the region.21

The Monroe Doctrine provided the Roosevelt administration with a diplomatic and international legal tradition through which information technology could assert a U.S. correct and obligation to intervene in the hemisphere. The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine asserted that the United States wished to promote stable, prosperous states in Latin America that could live up to their political and financial obligations. Roosevelt declared that "wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized club, may finally require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the U.s. cannot ignore this duty."22 President Monroe declared what Europeans could not practise in the Western Hemisphere; Roosevelt inverted his doctrine to legitimize direct U.S. intervention in the region.23

Though aggressive and bellicose, Roosevelt did not necessarily advocate expansion by military strength. In fact, the president insisted that in dealings with the Latin American nations, he did non seek national glory or expansion of territory and believed that war or intervention should be a terminal resort when resolving conflicts with problematic governments. According to Roosevelt, such actions were necessary to maintain "order and civilization."24 So once again, Roosevelt certainly believed in using military power to protect national interests and spheres of influence when admittedly necessary. He also believed that the American sphere included not simply Hawaii and the Caribbean area merely likewise much of the Pacific. When Japanese victories over Russia threatened the regional balance of ability, he sponsored peace talks between Russian and Japanese leaders, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1906.

V. Women and Imperialism

With much satisfaction, Columbia puts on her "Easter Bonnet," a chapeau shaped like a warship and labeled World Power. By 1901, when this political drawing was published, Americans felt confident in their country'due south position every bit a earth leader. Wikimedia.

Debates over American imperialism revolved around more than but politics and economics and national self-interest. They also included notions of humanitarianism, morality, religion, and ideas of "civilization." And they included meaning participation by American women.

In the fall of 1903, Margaret McLeod, historic period twenty-one, originally of Boston, constitute herself in Australia on family business and in demand of income. Fortuitously, she made the acquaintance of Alexander MacWillie, the top salesman for the H. J. Heinz Visitor, who happened to be looking for a young lady to serve as a "demonstrator" of Heinz products to potential consumers. McLeod proved to be such an attractive purveyor of India relish and baked beans that she accompanied MacWillie on the rest of his bout of Commonwealth of australia and continued on to South Africa, India, and Japan. Wherever she went, this "dainty young daughter with golden hair in white cap and tucker" drew attention to Heinz's products, but, in a much larger sense, she was also projecting an prototype of eye-grade American domesticity, of pure womanhood. Heinz saw itself not merely as purveying economical and healthful foodstuffs—information technology was bringing the blessings of civilisation to the world.25

When commentators, such as Theodore Roosevelt in his speech on "the strenuous life," spoke about America's overseas ventures, they generally gave the impression that this was a strictly masculine enterprise—the work of soldiers, sailors, government officials, explorers, businessmen, and scientists. Simply in fact, U.Due south. imperialism, which focused as much on economic and cultural influence as on military or political power, offered a range of opportunities for white, eye-class, Christian women. In improver to working as representatives of American business organisation, women could serve as missionaries, teachers, and medical professionals, and every bit artists and writers they were inspired by and helped transmit ideas nearly imperialism.

Moreover, the rhetoric of civilization that underlay imperialism was itself a highly gendered concept. According to the racial theory of the day, humans progressed through hierarchical stages of civilization in an orderly, linear fashion. Only Europeans and Americans had attained the highest level of civilization, which was superficially marked by whiteness but likewise included an industrial economy and a gender partition in which men and women had diverging but complementary roles. Social and technological progress had freed women of the burdens of physical labor and elevated them to a position of moral and spiritual authorization. White women thus potentially had important roles to play in U.S. imperialism, both as symbols of the benefits of American civilization and as vehicles for the transmission of American values.26

Civilization, while often cloaked in the language of morality and Christianity, was very much an economic concept. The stages of civilisation were primarily marked past their economic grapheme (hunter-gatherer, agricultural, industrial), and the consumption of industrially produced commodities was seen as a central moment in the progress of "savages" toward civilized life. Over the class of the nineteenth century, women in the Due west, for instance, had get closely associated with consumption, particularly of those bolt used in the domestic sphere. Thus it must have seemed natural for Alexander MacWillie to hire Margaret McLeod to "demonstrate" ketchup and chili sauce at the same time as she "demonstrated" white, centre-course domesticity. By adopting the use of such progressive products in their homes, consumers could potentially absorb fifty-fifty the virtues of American civilization.27

In some means, women'due south work in support of imperialism tin can be seen as an extension of the kind of activities many of them were already engaged in among working-class, immigrant, and Native American communities in the The states. Many white women felt that they had a duty to spread the benefits of Christian civilization to those less fortunate than themselves. American overseas ventures, then, merely expanded the scope of these activities—literally, in that the geographical range of possibilities encompassed practically the unabridged world, and figuratively, in that imperialism significantly raised the stakes of women's piece of work. No longer only responsible for shaping the next generation of American citizens, white women now had a crucial role to play in the maintenance of civilisation itself. They too would aid determine whether civilization would continue to progress.

Of form, not all women were agile supporters of U.Due south. imperialism. Many actively opposed it. Although the most prominent public voices confronting imperialism were male, women fabricated up a large proportion of the membership of organizations like the Anti-Imperialist League. For white women like Jane Addams and Josephine Shaw Lowell, anti-imperialist activism was an outgrowth of their work in opposition to violence and in support of commonwealth. Black female activists, meanwhile, generally viewed imperialism as a form of racial antagonism and drew parallels betwixt the treatments of African Americans at home and, for example, Filipinos away. Indeed, Ida B. Wells viewed her anti-lynching campaign as a kind of anti-imperialist activism.

VI. Immigration

For Americans at the turn of the century, imperialism and clearing were two sides of the same coin. The involvement of American women with imperialist and anti-imperialist activity demonstrates how foreign policy concerns were brought domicile and became, in a sense, domesticated. Information technology is too no coincidence that many of the women involved in both imperialist and anti-imperialist organizations were also concerned with the plight of new arrivals to the The states. Industrialization, imperialism, and immigration were all linked. Imperialism had at its core a desire for markets for American goods, and those appurtenances were increasingly manufactured by immigrant labor. This sense of growing dependence on "others" every bit producers and consumers, along with doubts nearly their capability of absorption into the mainstream of white, Protestant American society, caused a groovy deal of feet amid native-born Americans.

Betwixt 1870 and 1920, over xx-five million immigrants arrived in the United States. This migration was largely a continuation of a procedure begun earlier the Civil War, though by the turn of the twentieth century, new groups such every bit Italians, Poles, and Eastern European Jews made up a larger pct of the arrivals while Irish and German numbers began to dwindle.

Although the growing U.Due south. economy needed large numbers of immigrant workers for its factories and mills, many Americans reacted negatively to the arrival of so many immigrants. Nativists opposed mass immigration for diverse reasons. Some felt that the new arrivals were unfit for American republic, and that Irish or Italian immigrants used violence or bribery to corrupt municipal governments. Others (often before immigrants themselves) worried that the inflow of even more immigrants would issue in fewer jobs and lower wages. Such fears combined and resulted in anti-Chinese protests on the Westward Coast in the 1870s. Still others worried that immigrants brought with them radical ideas such equally socialism and communism. These fears multiplied after the Chicago Haymarket affair in 1886, in which immigrants were defendant of killing police officers in a bomb nail.28

Nativist sentiment intensified in the late nineteenth century as immigrants streamed into American cities. Uncle Sam's Lodging House, published in 1882, conveys this anti-immigrant attitude, with caricatured representations of Europeans, Asians, and African Americans creating a chaotic scene. Wikimedia.

In September 1876, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, a member of the Massachusetts Lath of State Charities, gave an address in support of the introduction of regulatory federal immigration legislation at an interstate conference of charity officials in Saratoga, New York. Immigration might bring some benefits, but "it as well introduces disease, ignorance, crime, pauperism and idleness." Sanborn thus advocated federal action to stop "indiscriminate and unregulated immigration."29

Sanborn's address was aimed at restricting only the clearing of paupers from Europe to the East Coast, but the idea of immigration restrictions was mutual across the United States in the late nineteenth century, when many variously feared that the influx of foreigners would undermine the racial, economic, and moral integrity of American society. From the 1870s to the 1920s, the federal authorities passed a series of laws limiting or discontinuing the immigration of particular groups, and the United States remained committed to regulating the kind of immigrants who would join American society. To critics, regulations legitimized racism, grade bias, and ethnic prejudice every bit formal national policy.

The first move for federal clearing control came from California, where racial hostility toward Chinese immigrants had mounted since the midnineteenth century. In addition to accusing Chinese immigrants of racial inferiority and unfitness for American citizenship, opponents claimed that they were also economically and morally corrupting American gild with cheap labor and immoral practices, such as prostitution. Immigration restriction was necessary for the "Caucasian race of California," as one anti-Chinese political leader declared, and for European Americans to "preserve and maintain their homes, their business, and their high social and moral position." In 1875, the anti-Chinese cause in California moved Congress to pass the Page Act, which banned the entry of convicted criminals, Asian laborers brought involuntarily, and women imported "for the purposes of prostitution," a stricture designed chiefly to exclude Chinese women. So, in May 1882, Congress suspended the immigration of all Chinese laborers with the Chinese Exclusion Act, making the Chinese the first immigrant group field of study to access restrictions on the basis of race. They became the first illegal immigrants.30

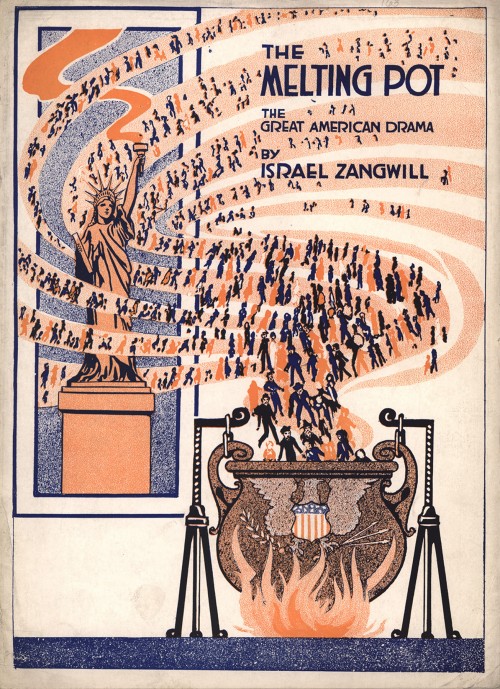

The thought of America as a "melting pot," a metaphor common in today's parlance, was a way of arguing for the ethnic assimilation of all immigrants into a nebulous "American" identity at the turn of the 20th century. A play of the same proper noun premiered in 1908 to great acclamation, causing even the old president Theodore Roosevelt to tell the playwright, "That's a great play, Mr. Zangwill, that's a great play." Cover of Theater Program for Israel Zangwill'due south play "The Melting Pot", 1916. Wikimedia.

On the other side of the country, Atlantic Seaboard states also facilitated the formation of federal clearing policy. Since the colonial menstruation, East Coast states had regulated clearing through their own passenger laws, which prohibited the landing of destitute foreigners unless shipmasters prepaid certain amounts of money in the support of those passengers. State-level control of pauper immigration adult into federal policy in the early 1880s. In Baronial 1882, Congress passed the Immigration Act, denying admission to people who were non able to support themselves and those, such as paupers, people with mental illnesses, or bedevilled criminals, who might otherwise threaten the security of the nation.

The category of excludable people expanded continuously afterward 1882. In 1885, in response to American workers' complaints virtually cheap immigrant labor, Congress added foreign workers migrating under labor contracts with American employers to the list of excludable people. Vi years later, the federal government included people who seemed likely to become wards of the state, people with contagious diseases, and polygamists, and made all groups of excludable people deportable. In 1903, those who would pose ideological threats to American republican commonwealth, such as anarchists and socialists, also became the subject of new immigration restrictions.

Many immigration critics were responding to the shifting demographics of American immigration. The heart of immigrant-sending regions shifted from northern and western Europe to southern and eastern Europe and Asia. These "new immigrants" were poorer, spoke languages other than English, and were likely Catholic or Jewish. White Protestant Americans typically regarded them as inferior, and American immigration policy began to reflect more explicit prejudice than always before. One restrictionist declared that these immigrants were "races with which the English-speaking people have never hitherto alloyed, and who are most alien to the peachy body of the people of the United States." The increased immigration of people from southern and eastern Europe, such as Italians, Jews, Slavs, and Greeks, led directly to calls for tighter restrictive measures. In 1907, the immigration of Japanese laborers was practically suspended when the American and Japanese governments reached the so-called Gentlemen's Agreement, co-ordinate to which Japan would end issuing passports to working-class emigrants. In its forty-ii-volume report of 1911, the U.S. Clearing Commission highlighted the impossibility of incorporating these new immigrants into American club. The study highlighted their supposed innate inferiority, asserting that they were the causes of ascent social issues in America, such every bit poverty, criminal offense, prostitution, and political radicalism.31

The assault against immigrants' Catholicism provides an splendid example of the challenges immigrant groups faced in the United States. By 1900, Catholicism in the United states had grown dramatically in size and diversity, from 1 percent of the population a century earlier to the largest religious denomination in America (though however outnumbered by Protestants as a whole). As a result, Catholics in America faced two intertwined challenges: one external, related to Protestant anti-Catholicism, and the other internal, having to do with the challenges of assimilation.

Externally, the Church building and its members remained an "outsider" religion in a nation that continued to see itself as culturally and religiously Protestant. Torrents of anti-Catholic literature and scandalous rumors maligned Catholics. Many Protestants doubted whether Catholics could ever brand loyal Americans because they supposedly owed primary allegiance to the pope.

Internally, Catholics in America faced the question every immigrant grouping has had to answer: to what extent should they get more similar native-built-in Americans? This question was particularly acute, every bit Catholics encompassed a variety of languages and customs. Beginning in the 1830s, Cosmic immigration to the Us had exploded with the increasing arrival of Irish and German language immigrants. Subsequent Catholic arrivals from Italy, Poland, and other Eastern European countries chafed at Irish dominance over the Church building hierarchy. Mexican and Mexican American Catholics, whether contempo immigrants or incorporated into the nation after the Mexican-American War, expressed similar frustrations. Could all these unlike Catholics remain part of the same Church?

Cosmic clergy approached this situation from a variety of perspectives. Some bishops advocated rapid assimilation into the English-speaking mainstream. These "Americanists" advocated an end to "indigenous parishes"—the unofficial exercise of permitting separate congregations for Poles, Italians, Germans, so on—in the belief that such isolation merely delayed immigrants' entry into the American mainstream. They predictable that the Catholic Church could thrive in a nation that espoused religious freedom, if only they assimilated. Meanwhile, however, more conservative clergy cautioned against assimilation. While they conceded that the United States had no official religion, they felt that Protestant notions of the separation of church and state and of licentious individual freedom posed a threat to the Catholic faith. They further saw ethnic parishes as an constructive strategy protecting immigrant communities and worried that Protestants would apply public schools to attack the Catholic faith. Somewhen, the head of the Catholic Church building, Pope Leo XIII, weighed in on the controversy. In 1899, he sent a special letter (an encyclical) to an archbishop in the U.s.a.. Leo reminded the Americanists that the Cosmic Church was a unified global body and that American liberties did not give Catholics the freedom to alter church teachings. The Americanists denied any such intention, but the bourgeois clergy claimed that the pope had sided with them. Tension between Catholicism and American life, still, would continue well into the twentieth century.32

The American encounter with Catholicism—and Catholicism'due south come across with America—testified to the tense relationship betwixt native-born and strange-born Americans, and to the larger ideas Americans used to situate themselves in a larger earth, a world of empire and immigrants.

VII. Decision

While American imperialism flared most brightly for a relatively cursory time at the turn of the century, new imperial patterns repeated onetime practices and lived on into the twentieth century. Simply suddenly the United States had embraced its cultural, economic, and religious influence in the world, along with a newfound armed services power, to exercise varying degrees of control over nations and peoples. Whether every bit formal subjects or unwilling partners on the receiving stop of Roosevelt's "big stick," those who experienced U.South. expansionist policies confronted new American ambitions. At dwelling house, debates over immigration and imperialism drew attending to the interplay of international and domestic policy and the means in which imperial actions, practices, and ideas affected and were afflicted by domestic questions. How Americans thought nearly the disharmonize in the Philippines, for example, was affected past how they approached immigration in their own cities. And at the turn of the century, those thoughts were very much on the minds of Americans.

VIII. Chief Sources

- William McKinley on American Expanionism (1903)

After the surrender of the Spanish in the Castilian-American War, the Usa assumed control of the Philippines and struggled to contain an anti-American insurgency.

2. Rudyard Kipling, "The White Man'south Burden" (1899)

As the United states waged war against Filipino insurgents, the British author and poet Rudyard Kipling urged the Americans to take up "the white man's burden."

3. James D. Phelan, "Why the Chinese Should Be Excluded" (1901)

James D. Phelan, the mayor of San Francisco, penned the post-obit article to drum up support for the extension of laws prohibiting Chinese immigration.

4. William James on "The Philippine Question" (1903)

Many Americans opposed imperialist actions. Here, the philosopher William James explains his opposition in the light of history.

v. Mark Twain, "The War Prayer" (ca.1904-five)

The American writer Marker Twain wrote the post-obit satire in the glow of America's imperial interventions.

6. Chinese Immigrants Confront Anti-Chinese Prejudice (1885, 1903)

Mary Tape, a Chinese immigrant mother, fought for her girl, Mamie Record, to integrate public schools in California. The instance, Tape v. Hurley (1885), reached the California Supreme Court in 1885 and, despite a favorable ruling for Tape, the San Francisco Board of Didactics built a segregated Chinese school which Mamie Tape was forced to attend. In the following letter of the alphabet, Mary Tape protested the deprival of her daughter'due south entry to Spring Valley School; Lee Chew immigrated from China at the age of 16. He worked every bit a domestic retainer for an American family unit in San Francisco, started a laundry concern, and later ran an importing business organisation in New York City. In the following passage, he attacked anti-Chinese prejudice in the United States.

seven. African Americans Debate Enlistment (1898)

Thousands of African-American troops served in in the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. Confronted with racial violence and discrimination at home, they did so with a mix of promise, skepticism, satisfaction, and thwarting. Hither, the Indianapolis Freeman reports on recruiting efforts in Hartfod, Connecticut.

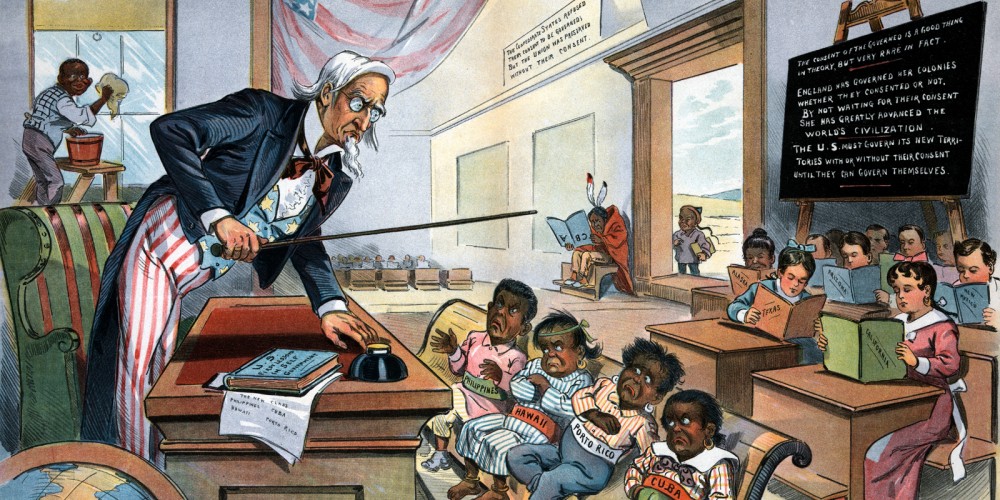

8. Schoolhouse Begins (1899)

In this 1899 drawing published, Uncle Sam lectures his new students: The Philippines, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and, Cuba. Past and potentially hereafter U.S. acquisitions fill up the residual of the classroom.

9. "Declined With Thanks" (1900)

In this political cartoon, tailor President McKinley measures an obese Uncle Sam for larger vesture, while Anti-Expansionists like Joseph Pulitzer unsuccessfully offer Sam a weight-loss elixir. As the nation increased its imperialistic presence and mission, many like Pulitzer worried that America would grow too large for its own good.

9. Reference Textile

This chapter was edited by Ellen Adams and Amy Kohout, with content contributions past Ellen Adams, Alvita Akiboh, Simon Balto, Jacob Betz, Tizoc Chavez, Morgan Deane, Dan Du, Hidetaka Hirota, Amy Kohout, Jose Juan Perez Melendez, Erik Moore, and Gregory Moore.

Recommended citation: Ellen Adams et al., "American Empire," Ellen Adams and Amy Kohout, eds., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the The states, 1880–1917. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Brooks, Charlotte. Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Gabaccia, Donna. Strange Relations: American Clearing in Global Perspective. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Greene, Julie. The Culvert Builders: Making America's Empire at the Panama Canal. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Guglielmo, Thomas A. White on Arrival: Italians, Race, Color, and Power in Chicago, 1890–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Harris, Susan 1000. God's Arbiters: Americans and the Philippines, 1898–1902. New York: Oxford University Printing, 2011.

- Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Printing, 1988.

- Hirota, Hidetaka. Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of American Immigration Policy. New York: Oxford University Printing, 2016.

- Hoganson, Kristin. Consumers' Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

- Hoganson, Kristin 50. Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Barbaric Virtues: The Usa Encounters Foreign People at Home and Abroad, 1876–1917. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

- Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a Unlike Colour: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Kaplan, Amy. The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.Southward. Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Kramer, Paul A. The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. Chapel Hill: University of Northward Carolina Press, 2006.

- Lafeber, Walter. The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1963.

- Lears, T. J. Jackson. Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modernistic America, 1877–1920. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.

- Linn, Brian McAllister. The Philippine War, 1899–1902. Lawrence: University Printing of Kansas, 2000.

- Love, Eric T. 50. Race over Empire: Racism and U.S. Imperialism, 1865–1900. Chapel Hill: University of Due north Carolina Press, 2004.

- Pascoe, Peggy. What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Perez, Louis A., Jr. The War of 1898: The The states and Cuba in History and Historiography. New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Printing, 2000.

- Renda, Mary. Taking Haiti: Armed forces Occupation and the Culture of US Imperialism, 1915–40. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Rosenberg, Emily S. Spreading the American Dream: American Economic and Cultural Expansion, 1890–1945. New York: Hill and Wang, 1982.

- Silbey, David. A State of war of Borderland and Empire: The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

- Wexler, Laura. Tender Violence: Domestic Visions in an Age of US Imperialism. Chapel Hill: University of Due north Carolina Printing, 2000.

- Williams, William Appleman. The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, 50th Anniversary Edition. New York: Norton, 2009 [1959].

Notes

Source: https://www.americanyawp.com/text/19-american-empire/

Postar um comentário for "In the Reading, Virtues Are Described as a ___________ Between ___________ & ______________?"